|

SUMMARY:

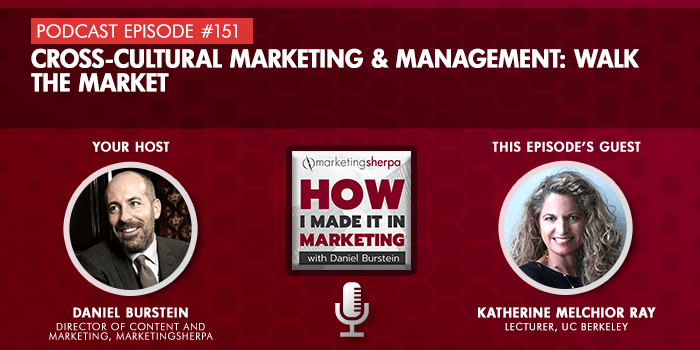

In this episode, I talked to Katherine Melchior Ray, faculty member and lecturer at the University of California Berkeley Haas School of Business, and author of the book ‘Brand Global, Adapt Local: How to build brand value across cultures.’ Listen now to get lessons about human-centered marketing, global branding, and cultural adaptation. |

Action Box: AI Executive Lab

Join us for ‘AI Executive Lab: Transform billable hours into scalable AI-powered products’ on September 10th at 2 pm EDT. Register here.

Data, data everywhere, but not a drop of insight.

Excuse my remixing of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, but doesn’t it feel that way when staring at a dashboard sometimes.

We have so much data – and frankly, our competitors probably have a lot of the same data – but can we turn those numbers into real insights to better serve a customer?

Here’s one way to do it, that I read in a recent podcast guest application, but you have to close your laptop first – “Walk the market.”

To hear the story behind that lesson, along with many more lesson-filled stories, I talked to Katherine Melchior Ray, faculty member and lecturer at the University of California Berkeley Haas School of Business, and author of the book ‘Brand Global, Adapt Local: How to build brand value across cultures.’

Berkeley Haas ranked No. 8 among U.S. business schools in the 2025 Financial Times Global MBA Ranking.

During her career, Ray managed teams up to 150 and reported to CEOs in Germany, France, Japan, and the US

Hear the full episode using this embedded player or by clicking through to your preferred audio streaming service using the links below it.

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Amazon Music

Curiosity provides infinite fuel. It stimulates interest, exploration, and knowledge. In college, Ray took a class on World War II that explored Pearl Harbor. The professor explained that this risky act arose from Japanese ethnocentric insecurity. Ray found the idea odd, that a culture could be insecure versus another culture, so she wanted to learn more about it.

In a subsequent class on Japanese art and architecture, she found the centuries-old comedic theatre, Noh Kyogen, to be both ancient and very modern. The abstract movements reminded her of modern dance in their enigmatic expressions.

Curiosity about Japan propelled her to live and work there three different times.

After college, she worked for a Japanese TV network where she learned to satisfy the Japanese viewing public. Their curiosity about the world, combined with extremely high quality expectations, taught her to market to this lucrative consumer with description and detail.

Her curiosity about the culture helped her understand how it was changing. Louis Vuitton sent her to Japan again years later to help them explain the massive changes in their most profitable market. She saw an evolution of the past and a forerunner of the future. The country that had limitless appetite for luxury goods was becoming satiated with omnipresent logos.

Louis Vuitton's over-dependence on fashion was hurting their classic business, so she sought to rebalance their focus between authenticity and innovation and got Antoine Arnault on board with a new approach. She appealed to Paris, and the Art of Travel campaign – in which Mikhail Gorbachev, Andre Agassi, and Steffi Graf were photographed by Annie Liebowitz – was born.

The third time she moved to Japan was to become CMO of Shiseido to transform a 150-year-old Japanese company into a global luxury marketing organization. To take their rightful place alongside – dare she say above – K beauty, they had to explain to the world what made Japanese beauty uniquely powerful. The Japanese understood it, but they could not articulate its enigmatic qualities.

Her curiosity helped her make the invisible visible to explain how Shiseido products please all five senses through art and science, winning awards in both innovation and art design.

While many people pursue jobs for business opportunities, Ray encourages people to follow their interests for longer-term fulfillment.

Ray’s parents loved history, but it wasn’t until her senior year in high school in Modern European History, where Steve Henrikson inspired her understanding of the past to interpret the present. History teaches us to notice and narrate context. Trends, values, and beliefs are the threads that weave the fabric of a particular era, shaping not only what people want, but why they want it and how to incite action.

Studying history in college helped her learn to interpret and then to shape culture. What are the underlying currents of ideas and values pushing cultural change? Where did they come from? This discipline teaches not only the skills to understand our world, but to conceive marketing strategies and craft the stories that bring them to life.

Leveraging history – of a brand, of its birth in a specific time and culture – creates value.

The most iconic companies didn’t simply emerge from economic opportunity – they were born of cultural moments. Levi Strauss created riveted denim for California gold miners. Coca-Cola began in 1886 as a temperance tonic. Nike’s waffle sole emerged during the 1970s jogging boom. These brands were more than business ideas – they were cultural responses to the needs, values, and aspirations of their time.

She learned from the best of them how to lean into history. At Louis Vuitton, she saw how the brand anchored itself in its origins – investing in the Vuitton home in Asnières, just outside Paris. In the leafy suburb, a special-order atelier operates alongside a living museum of the brand. When clients or journalists are invited to dine in the original family salon, they don’t just see a brand – they feel its heritage, relevance, and enduring vitality.

So, when she was hired by Gucci to refocus a brand losing its way with commercial logos and anglicized product names, she turned to history for inspiration. She went searching in its Florence archives. In dimly lit, steamy, and stuffy old rooms in a second-story apartment, she uncovered early scarf sketches and one of the first 1930’s newspaper campaigns with the headline “Regali per Tutti.”

That discovery inspired her to double down on their origin story, so they rebranded a new Japan-only jewelry line – featuring interlocking GG’s and a heart – as ICON AMOR, in honor of the creative director Frida Giannini’s home in Rome. That revival eventually helped pave the way for Gucci’s now-iconic archives near its Milan headquarters.

With a professional life that spans five industries and four countries, Ray has worked with diverse teams in the US, Japan, France and Germany and for 18 bosses of seven different nationalities (at last count!) Each time, she learned to understand their expectations – and to adapt hers. She’s proud to say she’s still in touch with colleagues from her first role in Japan when she was 22 years old and from each company and country in between.

Relationships are important to her. Her network has anchored her and helped her find new opportunities. But it was while teaching global marketing at Berkeley Haas, that she learned how unique this is to her American self.

While gaining the fundamentals of global marketing, she wants the graduate students to learn global teamwork as well. She has them take the GlobeSmart cultural assessment and teaches Geert Hofstede’s research on cross-cultural groups and organizations, to help them understand how their work and communication preferences differ from one another, usually related to their cultural upbringing.

In using herself as an example, she discovered her preferences are not typically American.

Especially on the cultural dimension of “Transactional vs Relational,” her personal preferences are closer to those of Japan than the US. Nearly all other countries, in fact, place a higher priority on relationships than the US, which is notoriously transactional. Recognizing that humans are relational beings helps us both lean into their emotional instincts and gain the rewards of long-term connections.

via Konishi-san, Director Business Development, Fujisankei International

Konishi-san was Ray’s first boss after she relocated to the New York office of the Japanese media conglomerate she worked for in Japan. It was the 1990’s and her job was to find American brands that would appeal to a Japanese audience for a national TV program and help export their goods.

While they scoured newspapers, magazines and trend reports for news, he encouraged her to “walk the market.” He recommended window shopping the trendy department stores, meandering up-and-coming neighborhoods, seeing what people were wearing, using and wanting. That advice has served her well over the years. Reports are helpful, but someone else is framing the trend. Sometimes it takes fresh eyes to see something hiding in plain sight.

After six to eight months, when she wanted to visit Japan and see the market evolution, he told her to figure out a compelling business reason. That lesson taught her how to connect her personal goals to corporate ones and a future where companies hired her to explore the world with her family.

via Gun Denhart, founder and CEO, Hanna Andersson

Swedish-born Gun Denhart hired Ray to build the international business for Denhart’s startup children’s clothing company in Portland, Oregon. After working for a large Japanese corporation, the cultural change nearly gave her whiplash. Rather than focusing on formality and hierarchy, Denhart focused on finance and humanity. She infused the company with her Swedish values of equality, open-communication and work-life balance.

Ray’s first child was born while working in New York for the Japanese company. She received 12 weeks maternity leave only because President Clinton had just signed the Family and Medical Leave Act. Only two years later, her second child was born while she worked for Denhart, who didn’t care how long she stayed home with the baby.

After only eight weeks, she came into the office for a meeting – with the baby in a car seat – and no one batted an eye. Denhart taught her firsthand to infuse a founder’s values into the brand and the company culture, how embedding brand values towards employees as well as customers strengthens the organization and the brand.

via Yves Carcelle, CEO of Louis Vuitton

Ray was hired by Carcelle to run marketing in Japan. This incredible businessperson was also an amazing human being who treated everybody the same, whether it was his boss, Bernard Arnault, his direct reports, or custodial staff. He traveled the world yet recalled the names of their Ginza store employees.

He evolved the brand from its legacy roots of designing wooden trunks and handbags into the world of fashion by hiring Marc Jacobs as its first creative director and inspired teams around the world to create similar breakthrough ideas, for example partnering with artists like Takashi Murakami. He both pushed them to think out of the box yet held them in line with clear brand beliefs that wouldn’t bend.

When Ray managed to lure Madonna herself into a Louis Vuitton store for the first time to pick out items, Carcelle would not allow her to write off the cost of the items Madonna selected for herself and her children Lourdes Leon and Rocco Ritchie. “Louis Vuitton doesn’t discount.”

On the flip side, after she presented a tight budget in a tense meeting with a half-dozen finance managers for their parent company LVMH at their Paris headquarters, he turned and asked her, “What would you do if you had another 5 million Euros?”

After his untimely early death in Paris, funeral attendees told her the most moving tribute came from an unlikely source: the building janitor who said that Monsieur Carcelle always said goodnight to him as he was usually the last one leaving the building.

Subscribe to the MarketingSherpa email newsletter to get more insights from your fellow marketers. Sign up for free if you’d like to get more episodes like this one.

This podcast is not about marketing – it is about the marketer. It draws its inspiration from the Flint McGlaughlin quote, “The key to transformative marketing is a transformed marketer” from the Become a Marketer-Philosopher: Create and optimize high-converting webpages free digital marketing course.

Not ready for a listen yet? Interested in searching the conversation? No problem. Below is a rough transcript of our discussion.

Katherine Melchior Ray: We're not machines, and your consumers can't behave like machines like we talked about with the Gucci story. They are. And they will forever be humans. And they are. We are motivated by people. Or, there's something called mirror neurons, which is all about how we relate to other people. And we literally form synapses in our brain when something touches us emotionally.

And so being able to grab those ideas and the strategies and, stories that have an emotional component and really touch people and communicate with them and their values, and to be able to do that across culture, involves layers and layers and layers of subjectivity, risk taking and creativity.

Outro: Welcome to how I made it in marketing. From marketing Sherpa, we scour pitches from hundreds of creative leaders and uncover specific examples, not just trending ideas or buzzword laden schmaltz. Real world examples to help you transform yourself as a marketer. Now here's your host. The senior director of Content and Marketing at Marketing Sherpa, Daniel Bernstein, to tell you about today's guest and.

Daniel Burstein: Data. Data everywhere, but not a drop of insight. Excuse my remixing of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, but doesn't it feel that way when staring at a dashboard? Sometimes we have so much data, and frankly, our competitors probably have a lot of the same data. But can we turn those numbers into real insights to better serve a customer? Here's one way to do it that I read in a recent podcast guest application.

But you have to close that laptop first. Walk the market. Here to share the story behind that lesson, along with many more lessons from honing this craft. We call marketing is Katherine Mulkey, a faculty member and lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley Haas School of Business and author of the book Brand Global Adapt Local How to Build Brand Values Across Cultures.

Thank you for joining me today, Katherine.

Katherine Melchior Ray: Thank you Daniel, I'm so excited to be here.

Daniel Burstein: All right. Well, that is that global branding in the title of the book. And when I went through your LinkedIn and your resume, I could say you have lived that. So let me tell the audience some of the roles that you have followed in your career. Katherine started as a marketing manager, TV producer and reporter at Fuji Sun Communications, Japan's largest media group.

She was women's footwear general manager at Nike, vice president of global marketing at Fashionable, part of Nordstrom, vice president, marketing communications for Louis Vuitton Japan. Executive director for strategic planning for Gucci in Japan Tommy Hilfiger is vice president of marketing, vice president, global luxury brands at Hyatt Hotels, CMO and SVP, Shiseido CMO of babble. And for the past four years at Berkeley, Berkley has ranked number eight among US business schools in the 2025 Financial Times Global MBA ranking, and during her career, Katherine managed teams of up to 150 and reported directly to CEOs in Germany, France, Japan and the US.

Katherine, there's a lot there. We're going to learn a lot in this episode, but let's start with today. What is your day like as a lecturer and faculty member?

Katherine Melchior Ray: Well, I love teaching because I get to impart ideas, knowledge and experience to the next generation. So my classes at Berkeley are probably 60, 40 international students. So I actually recently wrote an op ed about, about the way that international students benefit not only themselves, but their peers and bit local businesses because, they help us understand, other perspectives.

And it's in working together between all of the students because I have students from India, China, Taiwan, Brazil, Europe, America, it's hearing their stories. And, my basically helping extract the stories and give meaning and, comparison to those stories that I think we all learn so much.

Daniel Burstein: And we all operate in a global economy now, marketing Sherpa has readers and listeners the world over. So this is gonna be really interesting to learn about what you've learned from your global students, but also living all over the world and leading businesses. So let's start early in your career. One of your key lessons, you said was nurture your curiosity.

How did you learn this lesson?

Katherine Melchior Ray: You know, it's one of those things. You can't help it if it's in you. You just, have that ability. I think I was curious, about different cultures, actually, in high school. So I grew up in San Francisco, and, you know, San Francisco was the area where there was Russian Hill. And we went to Little Italy for the best espresso, and we went to the mission for burritos.

I mean, I kid you not like, I, we celebrated Chinese New Year just as much as we celebrated American New Year by going to the Empress of China. I remember it was at the top of a skyscraper in Chinatown. And, we always looked forward to having Peking Duck there. So I think, I was always curious about these different neighborhoods as a kid.

And then when I got to, when I got to college, I was taking a class on World War two, and the teacher spoke about how the Japanese, started Pearl Harbor as a reaction to, America and their feeling of a cultural insecurity that that was going to be the only way that they and that that that was going to be how they could basically knock out America.

And I was like, oh my God, I've been to Pearl Harbor, right? That is it's incredible what they did. But to think that that would actually knock out this huge country that was already involved in a war in Europe, and I was like, what? What is it? How can a have a can entire culture have a feeling of insecurity?

It just didn't make sense to me. So that led me on this quest to understand that psyche. So I took a class on Japanese history and art and architecture, and that's where then I discovered a whole nother, sort of slippery slope of Japanese, no Shogun, which is, a form of, of a of a Japanese art form.

Many people know of kabuki, which is very demonstrative, loud and colorful, but, no is actually the opposite. It's very simple. It's so simple that it seemed to me to be modern. And it's an ancient theater. So I was like, how can something so old, like, like thousands of years old, seem so modern? It was like modern art in movement.

You know how now, today you go to the museum and they have video and movement dance, and that's kind of modern art installations. And here's this really old art form that actually looked modern. So I was like, wow, it's kind of ending the continuum. That old becomes new again. And so that just led me onto this quest to learn more about the Japanese culture.

Daniel Burstein: Well, let's talk about your time in Japan and specifically Louis Vuitton. So I think it's interesting how these some of these things earlier in our life then lead to what are essentially brand campaigns. Can you take us into? I know you led a brand campaign with Amy Liebowitz, that appeal to Paris and the art of travel that was appealing to the Japanese market.

How did this nurturing your curiosity help you come up with work on that campaign with Annie Leibovitz? And what did you ultimately do with it?

Katherine Melchior Ray: Yeah. Okay. So I've lived in Japan three different times, which weirdly enough, is and is under three different emperors, but that's a whole nother story. So I, I was living in France when I met with I met Eve Castle, the CEO of Louis Vuitton, and when he found out, I spoke Japanese in addition to French, he just said, oh my God, you need to go to Japan.

Not to France, not to Paris. The job that I was interviewing you for and I was like, no, no, no, no, no, no, no. I live in France and my children are going to French schools and I'm going to stay in, in France. And he said, no, no, no, no, Japan is our largest, most profitable market.

And the numbers are not coming in the way they needed to. And I need you to go to and move your entire family from France to Japan. So, yeah, it was kind of one of those decisions of like, well, gosh, if you're going to go to Japan, you might also work for Louis Vuitton because it was by far and away the number one global luxury brand.

And if you're going to work for Louis Toy, you really should go to Japan because it's their largest, most profitable market. Okay, so it didn't take that much convincing, but we, uprooted ourselves. And when I got to Japan, I think my interest in Japanese history and culture served me very well because I could start to, through research, kind of stitch together these periods, after World War Two, of course, which I studied in college.

And this huge research sense that Japan had worked really, really hard on that had made it so, so wealthy, relatively speaking, that was the era when, Sony bought, Universal Pictures and they bought Rockefeller Center. And, actually, that was the that was when I was working for Fuji Television. So note the second time was the end of that era.

And so research started to show us that this psyche of hard work, determination and wanting to really, be a part of the global game was starting to turn, and consumers were kind of going, you know, everyone has the same luxury bag. I don't really want to have the same monogram on my bag that everyone else has.

Whereas previous to that, Japan was a country where, you know, you put a logo on it and it will sell. And so it was a much more subtle nuance evolution that was going on in the market. And I had to figure out what to do. So when your, so I was the only American, my team was all Japanese and obviously the headquarters was all French.

My, my CEO was Japanese. And we had to pore over this research to try to understand what was hiding in plain sight. And this is why I actually love research, because research will tell you a certain information, but it doesn't really read between the lines. I actually brought my knowledge of Japanese history and this kind of cultural awareness, ethnocentrism, insecurity to be able to understand that this, adoration of luxury was changing.

And we need to get that, we need that. And I could kind of understand it because I was a Westerner, so I didn't have that postwar catch up mentor city that had existed before. I was kind of in that next phase that Japan was coming to. And so, I realized what was happening then. So that's what's going on in research.

Then you look at your business and you say, okay, what's going on in our business? Well, our iconic bags, our speed, our keep, all the bags that have been selling for decades, were not selling the way they used to. And I did customer research and we showed consumers our latest advertising that had models in them, and they didn't know who these models were.

They meant nothing to them. They're like, okay, who cares? It's just another Western model. And I realized that we had we were out of balance. That we were we'd gotten too fashionable, we'd lost our tradition. We'd lost our iconic. And when you lose the value of your iconic products, you're losing your bread and butter. It's really very dangerous, for a large brand.

And it actually is what led me to create a concept that I call the brand fulcrum, and I call it that because I realized any strong brand has seemingly opposite, but importantly, complementary values that it has to, work on simultaneously. If you're only classic and you only talk about your history, you're kind of dull at the end of the day, you know, you can just the thing never changes if you're on the opposite side of this teeter totter and you're very innovative, but you're also always catching the less latest trend.

You're only as good as your last trend. Latest trend hits the market, so it's really having to use both ends of this fulcrum and making sure that your brand stays in the same place. So if you're too classic or conservative, you're dull. And if you're too trendy and innovative, then, you can't you don't have the value of your classics to be able to sustain the business over the long term.

So, I realized that what we needed to do in Japan was we had to reinvest in our history and in our storytelling about our classics. And so I started to call attention to this in Paris. Well, in Tokyo, we realized it. My CEO understood exactly what I was saying, and he agreed with me. And so we started to get Paris on our on our side, talking about how, the the future, the past.

Japan has always been considered kind of the pinnacle of luxury and at the far end of where luxury is going. And so if they are starting to move away from, the Yeezy logo products and the rest of the world may follow suit, and that we really needed to re anchor our history, Antoine Arnault had just come into the creative side of the brand, and he was actually very open minded, and he listened to this.

And so we talked about it, but they weren't ready to do it yet. So we faced an option of, are we going to do our own campaign in Japan? Okay, that would be getting beheaded, like they did to Marie-Antoinette. And I didn't really want to have that happen. So I, learned to bide my time a little bit.

But over, about over about a year or so with my research, people started to realize that this was actually a global need. And so that led to the global campaign card, the Art of travel, that, I mean, we could not have done such an incredible campaign by ourselves, even though Japan was such a powerful market for the brand.

But, led by Antoine and the Paris team, they hired Andy Liebowitz, and it was this beautiful re-envisioning of these campaigns that Louis Vuitton has done, over the years and over the decades of the art of travel. And it's where we started to talk again about how travel as a concept, not just literally going from one place to another, but of the kinds of journey that we take in our lives.

So we actually showcased, Gorbachev's, in a it's a famous scene of Gorbachev in the back of a car. And he's reading the newspaper and he has a really tall, suitcase. Or we did at the time, Andre Agassi and Steffi Graf were just getting together. And so we sort of talked. We had a scene with the two of them, not so much.

Nothing about them on the tennis courts, but it was about their love affair, of two people who've really fought their way to find not only success in their lives, but success in their love. So there were a lot of celebrities that we we, put in these scenes, and it was just so much more meaningful, to, to the brand and to our audience than a model carrying the latest bag.

Daniel Burstein: Yeah. And so when you're talking about culture and understanding commonly it's like case it seems like also understanding what happened before is essential. You mentioned another lesson. History is not just for school. So how did you learn this.

Katherine Melchior Ray: Yeah, I actually, you know, it's the kind of thing that you push back against that you end up embracing. I was my my parents loved history and they had all these huge nonfiction books on the coffee table. I was like, oh, it's like so heavy, you know, I just want the fashion magazines. Whereas I, I learned finally I had a history teacher in high school who helped us understand that history is not just about memorizing facts, but history is really teaching us to notice or even narrate eventually.

Context. That trends and values, beliefs are all the ways that change happens in a society. You have to learn to see those patterns and those threads because they're emerging over time. Change in culture doesn't happen overnight unless there's obviously a calamity like covet, which then, you know, you see the change happens. But even then, right, it took us a while to adapt and change.

And we're just we're just now really coming out of Covid with new behaviors that are not going back at all. But most change in cultures happens over time, and it's about being able to perceive those threads, over time. And then often there's some kind of an event that turns them into some, some intertwined crisis. At least that's how major change happens in terms of, like wartime history.

I studied wartime history. I was an American history major, and it just seemed like those were times of major change and crisis, and they were so much to learn about. Unfortunately, America has lots of wars to study. So, I had a lot of I had a lot of content there. So, yeah, I, I learned to appreciate history for that.

For those reasons of the fact that it gives you a framework if you will, to understand culture, and it gives you the skills to be able to create a narrative as to why something is happening. In the present, in terms of what happened in the past. But also I realized over time that that's an incredibly, applicable arts that's incredibly applicable to marketing.

So often people say to me, oh, you know, wow, how did you get to be a CMO? Of a two different industries in two different countries. And did you study communication? I said, no, I studied history, and I love this notion that, history, which I think especially today when we're so focused on Stem and science, which is very important to your point about data, the history actually helps give us a complementary skill to learn to be able to see, through around the data and to build the narrative that is so critical for it to make sense to us as humans.

Daniel Burstein: Well, and I loved history, too, because it's really just all stories, which is the same thing we do as marketers. So let's give the audience a bit of a specific example. So we've all taken history in high school on some level. I assume you specifically mentioned your senior year in high school. You took modern European history from Steve Hendrix, and then you also mentioned in your time working with Gucci how to refocus the brand.

And I would imagine modern European history would help you refocus the Gucci brand, at least having some understanding. So under can you give us a through line from modern European history in high school to rebranding or whatever you did with there with Gucci?

Katherine Melchior Ray: Yeah. Well, I think modern so modern European history helped me understand the power of history. I grew up in San Francisco, as I said, and I was surrounded by brands that represented history. You know, I mean, my first jeans were Levi's. So we all learned California history. And the 40 niners are football team, by the way. Who you know, with 40 niners were the gold diggers who came out and needed strong pants to be able to work in the mines.

And that's how Levi's created that. So the 40 niners, you know, Crocker Bank, Wells Fargo, which is where my parents bank was started because it was the, post office system, that went across the Continental Divide. So I realized that brands, emerged from culture and are very, very tied to culture and that they derive a lot of their value from culture, as I talked about with the Beatles.

So, after Louis Vuitton, I worked for Gucci and Gucci is another incredible brand with incredible history. And when I, when I was working for them, I came in and they said, oh, okay, Catherine, you know, you got to help us. We are seeing again a change in our market, and we have a really big launch coming up with a with a series of rings.

Every year in May, we launch a series of rings because a lot of people get engaged. Then, and for the first time, our sales have not been increasing. And so I said, okay, well, we don't have a lot of time. So show me the ring that you're planning on doing. And they showed me a ring that I kid you not.

It had interlocking GS and a heart on it. And they were going to call it Gucci. Love was like, okay guys, this is, not respecting the consumer, right? I mean, it is just so it's too obvious. It's too trite. There's no meaning there. I get it, I get it, you know, the interlocking GS have value and a heart has value.

But to throw those all in a ring and expect it to just do really well is, is the wrong expectation. It's the wrong approach. So I said, okay, what am I going to do? Where are we? I was again in Japan, and I so I knew about the history of how the Japanese consumer was moving away from simple messages.

But I had to figure out how to anchor this launch. Well, I went to Florence, the headquarters for, origin of of of Gucci. And I wanted to go to the archives and to learn about the history and all those days, the archives. And I kid you not, they were on the second floor of a non air conditioned old building in the middle of Florence.

And, there was one person working there and I, you know, came in. I'd come all the way from Japan. And I said, well, I'm just trying to find inspiration, of the brand. Like, I want to know more about it. I mean, obviously there were there were documents and papers that explain the history of the brand, but I needed something for this.

So, you know, there were a lot of prior fashion, clothes on models, but it was not a place, and customers didn't come there. The public didn't come there. Even internal people rarely went there. And there was also a file cabinet. And in this filing cabinet, you would open the drawers and there were just layers and layers and layers of these old prints of the old scarves.

So could you used to do these incredible, equestrian looking scarves, but again, interlocking GS and as I explored further on the wall, I saw a frame of an old advertisement. It was black and white, and it was from the newspaper in the 30s, in, in Italy. And it said, it said, the gala patootie, which means gifts for everybody.

It was just a newspaper ad, right? And it said, you know, Gucci didn't even have the interlocking GS at the time. And I was like, I can only patootie I know enough Italian to know that means gifts for all. And I was like, exactly. But I got a letter to the okay, we should like we should really?

You leverage this. This is our history, you know, what's this about gifting? So I started to realize there's a lot here in Italy and what we could do. Meanwhile, at the time, Free Frida Giani was our art director, and she was moving the creative headquarters, where she worked from, to Rome, because that was her hometown, and she was more inspired there.

And so we were redoing our flagship store in Rome. And so I was at Rome for another event, and I was thinking, you know, what is free to trying to teach me? And, you know, and so I was in Rome and I was looking all the signs of Rome at all my and I was thinking back to now my, my, my rings with the hearts on them.

And I was like, okay, Gucci. It's like, well, how do you say love in Italian? Because we have to get rid of the English. We've got to go more authentic. We've got to go back to the country of origin. And I realized that love is a more ammo for, and that that backwards is Roma. So Rome is literally, the word is love backwards.

So I suddenly had my idea and I realized that we would do this collection as a, as a gift from Frida Giannini herself to the Japanese audience in celebration of her love for her hometown where we were moving. The creative headquarters. And so suddenly now we had, icon Amore is what we called it icon, meaning the interlocking GS.

Or ammo, ammo r. And then I shot, I shot the campaign, in Rome with on these beautiful old cobblestone steps with the Colosseum in the background. And I got the team. While they couldn't change the product, they could expand it to a collection. So not only did we have yellow gold, but we had white gold and rose gold.

And so it was a collection of three rings in a in a, exclusive collection for Japan in honor of the celebration between Rome and Japan.

Daniel Burstein: So what you just said is everything I love about marketing, right? I mean, one is digging for that the heart of the story, which you did and the beautiful fashion there. But the other thing is the adding the value to the actual product itself. Right. So there's the actual real value that we deliver with our products and services, you know, whatever that may be.

But there's also the perceived value the customer has. And by bringing out that culture and heritage of Gucci, what was going on there? Not only did you obviously market and sell or whatnot, but whoever bought those products, they valued them more because they understood it on a deeper level. And that to me is the craft of marketing. So I love.

Katherine Melchior Ray: Absolutely. I completely agree with you. And it's why I think the front lines of marketing is always your service representatives, whether it's on the phone or in the store or, and the more that we recognize that these people are delivering the brand through conversation, the more you can leverage that incredible resource that they have because they're connect.

They're literally connecting with your audience. So the rest, you know, we spend all this money on our website and on communication and advertising and I think, you know, training and development and investing in that front line is incredibly valuable.

Daniel Burstein: Every customer touchpoint is a thing of value. And learning from those people and learning from all those around us. And one of the things, another key lesson you said is prioritize relationships. So how did you learn this lesson? To prioritize relationships?

Katherine Melchior Ray: Well, I think it's really what's kept me connected to people as I've lived around the world. So as you mentioned, I've, I've lived, across the US, in France, Germany and Japan. And my, my network has really anchored me. They've first of all, I think they've helped me find jobs. And when I think about the different jobs that I've had, most of them have, if not all of them have come through people I knew.

And if that sounds like, okay, I happen to have a great network, it's not that. It's that I would work with various people and I would just get my work done. But also it's about how you get your work done and how you connect with other people in order to get your work done. And when you value people that value keeps giving.

Even if one of you leaves the company, people remember that. And so as happens, people go from one company to another and they will see each other once again in another company or not. But if you need something, often you can go back to someone who's no longer even in your company or even in their country, the same country.

But if you help them, they'll try to help you. So I've I've learned that that's extremely important. Now, what's kind of funny about this is that I really prioritize relationships to the, to the point of sometimes I thought it was my detriment because if you lose a job, I'm crushed. And, you know, in marketing, the average time frame of a of a CMO is, I think, 18 months, something like that.

So you can't take it personally, but I would, and it was only when I started teaching MBA students about culture and in global marketing that I realized something about myself. So when there's, Austrian, anthropologist and business writer called Garrett Hofstetter, who studied cultures and he did the Six Dimensions of culture, and he realized that you can place cultures across these different places, across these six dimension.

There's no right or wrong. But there are ranges across these different ones. And they could be how hierarchical is a culture versus how egalitarian is it? And one of those is called is the culture very transactional or is it very relational? And when I plotted myself in one of these assessments to understand, you know, so if you look at Americans in general, they are very egalitarian.

They are very transactional. Time is money. You know, they're very focused on, getting things done. And in terms of like communication, are they direct or indirect? What's interesting, they are on the direct side, but it really depends where they are in the United States, in terms of actually maybe they're more indirect or passive aggressive, than direct.

But when I plotted myself, I didn't come up along a typical American profile. Like, well, that's kind of strange. So then I said, okay, well, I've spent a lot of time in Japan, I'm going to Japan. And so Japan was almost on an opposite kind of a curve than, than the US. And on the transactional versus relational, I actually matched up with Japan.

That's a consensus driven culture. So very, very aware of others wanting to make decisions through consensus. I'm not really always consensus driven, but I'm closer to that than I was to America. I then plotted the French culture, which I found out was kind of somewhere in between, not exactly. And I actually matched up pretty closely to the French culture.

And I realized growing up in San Francisco, I attended a French bilingual school. So that, school really, affects us much more than, than we think and that, perhaps my, my own personality and expectations for communication and how to work with others. Is, is was actually learned a lot in the school. But I learned that in terms of my relationships to of relationships, America is the most transactional culture in the world.

People say, okay, we're I'm, I'm only come in. So we can get this deal done. And then, like, when I'm going to land at the airport, I can be there at an hour. Hopefully I can get a flight out that night. Now, if you go to another culture where you're hoping to do a deal, they would probably not understand even what you're saying.

I always recommend to people, if you're going to another culture, to have a business discussion or negotiation, or try to do a deal, fly in the night before, go in the night before, have a meal, get to know people. Other cultures are all more relational than America, and it's hard for Americans to really understand what that means. But they feel like, oh, we're not going to deal a deal with someone we don't know and Americans are going to be.

I don't really want to waste my time, you know, we'll just have it all in a contract. Whereas in a lot of other cultures, a contract, you know, is the last part that comes. And honestly, they'd kind of expect you if you have a relationship to go beyond the contract.

Daniel Burstein: Yeah. You know, I was, interviewing a French executive and we were talking about how we learned some lessons from a customer and stuff and kind of stopped and he said, try to explain, like, look, we're at a conference. And so when you're at a conference with your customer, like you eat with them for hours, like you take them out to eat for hours and you like, you spend a lot of time with them and these these things come up and it's just, like you said, kind of a natural difference in how we act when we talk about these parties and relationships and the difference between transactional and some of these things, the relationships you

had that I'm the most interested in, I think our audience might be as well as with CEOs. And so I wonder what you learned from your time in these different cultures, and also just in your time in business on how to build those relationships with CEOs of different cultures?

Katherine Melchior Ray: Haha, gosh, I could write a whole nother book on that topic. I think you know, to I can't really say it's one thing or another. You've got to learn to understand the other person's expectations. So it really comes back to the higher calling of having a global mindset. And the most important part of a global mindset is an open mind.

So you have to be able to come in with an open mind to try to see the things that you can't really understand, because you might think, like I said, transactional or relational. I mean, who talks about that? Who says, oh, I'm transactional. Like, oh, I just want to get the job done. And just because I'm American doesn't mean that I'm transactional, right?

So you can't really, predict how a person is going to, want to work with you. So I think the key thing is to try to be explicit. One of the ideas that I love and that I teach, and that I wrote in my book, is the notion of culture as an iceberg. I don't know if you've ever heard this, but as soon as I say it, it seems to make sense to a lot of people, right?

The thing you see is the top. And that's the language, the dress, the food, the movies, all the things that we think about when we think about culture. But it's really, really, really important to remember that all of those things we see are infused with things you can't see. Silent expectations. Expectations of gender norms, concerns about timeliness.

You know what? On time means something different in different cultures. I change my watch when I fly to Tokyo. I have to set it ahead, because otherwise I will always be late in their eyes. And so, you know, all of these things are hiding under the water. And so what I try to tell people in working across cultures is you have to lower the water line.

You've got to learn to expose these silent expectations, hidden assumptions, so that everyone is working on, shared and explicit ideas. And I have, an example of that. I like to say like, what are the two most important words in French?

Daniel Burstein: Merci beaucoup.

Katherine Melchior Ray: Yeah. And I think you took French so that that's kind of two. But they're not the most important. They are important. And so it's not really what you think it will be. Most people say okay, merci. Or they say silver play, which means please, but that's more than two. So it, you know, one of the ideas is that it is Bonjour.

Hello. But it's not just Bonjour. What's the second one? It's Bonjour, monsieur or Bonjour, madame. And the reason I say that is because you need to acknowledge somewhat. Greetings are very important in a lot of cultures. You need to not only greet them, but you need to acknowledge them. So whether you are whether you're in buying a newspaper on the, or a book on the site, on the, on the side, or you have a worker coming into your house, you can't just say bonjour, you say monsieur or madame.

And what it does is it like opens doors to a relationship. It says, I see you and I recognize you, and that in that culture is kind of like, okay, now we can have a relationship. Now we can engage in something, even if you're just going to buy, you know, a stick of gum. I mean, really and if you don't say it and you say, you know, do you know where this is?

They will turn to you and say, Bonjour, meaning you did not bother me.

Daniel Burstein: You know where I see that's true. Like just even here in America is on slack sometimes, like slack or any whatever versions of that. I work remote. A lot of us work remote. Now. It can be so easy to go directly for that transactional. Okay, where does this thing do this? You know, and I work with a colleague who's also a good boss and good morning and this and that.

And he's kind of slowed me down a bit to say, you know what? We we don't want to, like get rid of those niceties just because we're trying to work remotely.

Katherine Melchior Ray: It depends on whom you're speaking to. You know, if you're in the US and people are just going back and forth, it's like, can you do this for me? Can you do that for me? BA ba ba. Like it's fast and efficient and that's our value system. But if you're speaking to someone.

Daniel Burstein: Something like you said, even in America, I feel like we can lose something. Yeah.

Katherine Melchior Ray: No, I mean, we can, but some people don't care about losing that. That's true. It's really. No, I mean, it goes back to everything, like knowing your audience, which is where we started with, you know, how do you work with CEOs of different cultures? And it's about understanding. I mean, look at some like you do in marketing, who's your audience?

Your audience is CEO. And what do what does she want? And, what are you going to deliver for? For them? So, and how do they want to work as a team? It's not easy. And I mean, I think I counted I had something like, you know, 15 CEOs of nine different nationalities.

Daniel Burstein: Okay, well, speaking of relationships, the whole second half of our episode is going to be about relationships, collaboration and people Katharine learned from. But first I should mention that the how I made it in Marketing podcast is brought to you by Mic Labs. I the parent company of Marketing Sherpa. You can turn your IP into a new revenue stream with Mic labs I you may qualify for a $5,000 voucher to build your first product on Mac Labs.

I talk to Mac Labs. I ask yourself, they'll give you all the details. You can do that at Mac labs.com/5 K voucher to learn details, requirements and answer the seven question voucher application. That's Mac Lab Comp five K voucher, mic labs E-commerce five K voucher. All right Katherine, so let's jump in to say as I mentioned the second half, we talk about, you know, the first half, some of the things we built, the second half, some of the people we collaborated with learn from to build those things.

The first lesson you mentioned is Walk the Market and you said you learn this from Konishi San, the director of business development at Fuji San Kay International.

Katherine Melchior Ray: Yeah. So Connie son, he was such a sweet man. And so you have to picture this. I was working for a Japanese TV network, first in Tokyo, and after two years, I was sliding down the steep Japanese culture. And I didn't even know any foreigners. And I was like, okay, I got to get out of here.

So I took a transfer to New York, and instead I got to continue working on Japanese television shows. But I got to do it from New York City. So when I would walk into, our 53rd Street office, the elevators would open, and then I would just shift into Japanese, and I was like, oh, hi. God. I'm,

Which is like, hello to everybody. And, you know, you just go. It's just Japanese all day long. And we had an open office system where the manager would sit at the end, and all the desks were kind of lined up next to them in order of hierarchy. So Connie San was my first boss? He had he had come like, I don't know, he's trying to be a dentist.

And then he liked opera. And somehow he got into, the business side of television and was sent to New York. It worked for him because since he loved opera, he could go to see the Metropolitan Opera. And in fact, it was, again, this era was when the Japanese had, the real estate bubble brought a lot of, income and value to organizations.

So we had a lot of money and a lot of expense accounts, and we had a lot of visitors. So he bought eight, and I kid you not, eight subscriptions to the Metropolitan Opera for when we had guests, but we didn't have guests every single week. So otherwise he was like, hey, Catherine Cassadine was my name. You say, Catherine, bring your friends.

We have all these extra opera tickets. I would just call, you know, call friends. Is it anyone want to go see? You know, Luciano Pavarotti, in the opera tonight. So it was a very, very fun time. And lovely Cornish son would tell me my, my job at the time was finding stories to report back to Japanese television.

They wanted to know what was going on in New York. And what were the trends and, and what was happening. And so we, we bought trend reports. We got those and I read those and, you know, it was kind of a lot of stuff to get through. It wasn't giving me a sense of the pulse of the market.

And he said, what market? Get outside, get out of your office. Go window shopping, see what trends are being shown, see what people are wearing, see how they're talking. See, see if they're taking taxis or riding bikes, like, really go out and see what's going well, what's going on. And that advice is really served me well over the years.

I find that, don't get me wrong, reports are really helpful. I've used them and I've talked about them earlier on in the podcast. But someone else is framing the report. It's through someone else's eyes. And if you learn to observe and try to see the things that other people may not see, you can spot ideas. And that's that to me, is where the magic happens.

It's really being able to, spot things that other people aren't seeing and be able to recognize how to turn that into something else. I mean, I'll give you an example. When I was at Nike, I ran women's footwear for the U.S. and we were we were finally, for the first time, creating a women's insole. I kid you not.

Well, at the day in the day, women's footwear was seen as an afterthought. And then it was the day of, quote unquote, shrink it and pink it. Yeah, that was what I mean, I'm not kidding. That is what, Nike did for women's shoes. And yet we realized that women had twice as many knee injuries in sports, ACLs.

And I know because I've had I've had one. So I played varsity volleyball in college and I have it had an ACL and an MCL repair. And we learned this because of something called the Q angle, which is women have wider hips. Those wider hips put a disproportionate pressure on the outside of their knee, which is, which can be corrected with a balanced insole if you help, oppose that pressure, you can help balance that so that the knee is not under so much pressure.

So we had created this new insole, and I wanted to see what, our target audience thought. So I went with a, we had a do shoe was a cool looking shoe, and I brought it to some high school basketball girls. And I just we went and talked to them outside of New York City. And I said, well, you know, tell me about the sneakers you wear.

And they're like, well, you know, on the court, we always wear Nike. And I said, okay, that's nice. Great. What it why they said, well, because it's the best it has the best technical, the best technical, support. We don't think we're going to break our ankle. You know, we can rebound all that. And I said, but what do you mean by on the court?

And they said, well, yeah, on the court. And I said, well, what do you wear in the morning? Like, oh yeah, we wouldn't wear our Nike's. Well why not? So they said, yeah, we wear ordi. They've got much better colors. They're much cooler to wear. Okay. That was really hard to hear. So I said, okay, well, I understand what I want to show you something.

So I pulled out my shoe, my brand new shoe, and, I showed it to them and I showed it to them, like, you see, today in Shoe Falls, right? It's on the side. And if you go to Nike campus and you go to any shoe designer's office, they often have huge posters of cars because that's what inspires them.

They're always thinking about, okay, this is a really cool Porsche. Look at how aerodynamic dynamic it is. I want to make my shoe the same aerodynamic approach and color, and they could do more with the shoe than you can with a car. So in terms of design and creativity. So I showed it to them that way. And I said, what do you think about it?

Because that's how we looked at it at Nike around the table. And this girl said, hey, yeah, give it to me. So I gave her the shoe. They were just kind of looking at it. No comment. Not nothing yet. And she took the shoe. She stood up and she put the shoe on the ground and proceeded to look at it from above.

And I said like, oh my God, we have a problem. And I realized that women in that day of the shrink getting pink it were, buying the shoes, more so at department stores and at other kinds of stores where they're sold, not on the wall from the side, but in, round tables in pairs where they're looking at them from top down.

So most of women's shoes are sold that way. And so women were looking at shoes that way, even sports shoes. And so I realized no one said anything. There was no report that said, the woman put the shoe on the floor and stood up and saw that she was looking from the top down. But I saw that. And, and so did the designer.

And we both saw this and we realized, okay, we're looking at it all wrong. And this was in the United States with American consumers. And I had been a college athlete, too. But I hadn't dawned on me how much we had a blind spot in terms of how we were really trying to create something for a consumer that had different expectations and different shopping behaviors.

So not only did we change the design, but we opened distribution to the department stores.

Daniel Burstein: I mean, what a great insight into the customer. But let me ask you this. When you when I heard the welcome market story, this is the thing that most interests me. I wonder if it ever helped you internally with pitching or winning arguments, right? For example, when I interviewed Dave Anderson, the vice president of product marketing at Content Square, one of his lessons was telling stories with data creates internal momentum.

And kind of I said in the beginning, we all try to use data to build this case internally, but depending on who you're pitching to, you either their eyes roll or there's different numbers. Competing numbers. But I feel like having those specific insights of walking the market and seeing things could add that rich color to the data to be able to get you worked in some very large international organizations, to be able to win approval of the things you needed internally.

And so I just wonder if that walk the market approach, because when people are listening now, you know, I feel like not all of us, but a lot of us have become a bit of a hermit when it comes to marketing. We just have our, you know, eyes down. We're looking at the dashboard, we have all the data.

That's all we need. And we forget we need to go out there and actually talk to the customers or encourage people to do that. One of the things I think that would excite them is to to win approval internally. I just wonder if this approach has ever worked for you there.

Katherine Melchior Ray: It has worked. So another example I'll give you is, about Japan, right? So, most Japanese commute by foot and, you know, or like, like in New York, there's a good public system. So public transportation system. So they do that and it's looking at that so that when, when a customer says, you know, I got to get my I got to get my cell phone out of my foot.

So with the salary, what's called a salary, man. Oh, this is in the book. And it when a business person says, you know, I need to be able to access my phone quickly when you see the Japanese subway system and how people are pushed into them during maximum rush hour where you cannot move your arms.

I'm telling you, you can't move your arms wherever your arms are. They're stuck. Unless you're going to kind of inconvenience people and try to rearrange them. And any, any of your listeners who've been in Japan during rush hour know what I'm talking about. So when you realize that and you say and you understand the pressure that people feel, if there's a sales call to get their phone, you realize what what they're up against.

Whereas otherwise, like, you can think, oh, your bag is next to you in the car, or you know, it's on your desk, or is below at your feet. Like it's not that hard to really understand the context of what people are talking about is where it's really helpful to be able to know their lifestyle and get that get that framing of the, the, the, information that that puts meat on the bones.

Daniel Burstein: Are we need to know our customers. Well, of course, but here's another person we should know, the founder. So, you mentioned that you learn to infuse a founder's values into the brand. You learned this from Goon Den Hart, founder and CEO of Hanna Anderson. How did you learn this from Gun Den Heart?

Katherine Melchior Ray: Well, after working for Fuji TV in New York, I actually had my first child there, and, they followed the letter of the law, giving me 12 weeks of, child care, maternity care. And I love to go from there to a Swedish founder inspired child care company in Portland, Oregon. The the change was so radical, it nearly gave me whiplash.

So rather than focusing on formality and hierarchy, she really focused on. She was a great finance person, and she focused on humility and empathy and understanding her, her her customer. So the customer was it was a children's clothing company. So the customer was a was a mom. And so of she wanted to treat her employees, as who are moms in the same way she treat her customers, which great empathy, respect and flexibility.

They all wanted flexibility. So I had my second child working for her, and I thought, okay, I got to have 12 weeks, I can have 12 weeks. She said, no, take as much time as you need. I was responsible for international, so I was helping the company expand internationally. So, you know, calls at different times of day or night.

And she was absolutely, firm that I should take as much time as I needed. And what happened? I actually went in before the 12 weeks. She gave me so much flexibility and support that there was we had a really big meeting where we were talking to use USPS about creating a unique deal to ship, packages to different countries and they were flying in.

And so what did I do? I use my best judgment, and I brought my eight week old son in his car seat, and I just and this was way before Covid and work from home and, you know, people blending their lives together. This was in like the in the 1990s and I just brought my son in and I put him in his car seat in the corner of the room, and we had the whole meeting and it was really great.

And he was cute as could be, of course, wearing his Hannah Anderson jammies. But it made me realize that, first of all, there are no rules. Yes, we have laws and the laws are different in country from country to country, and businesses have to abide by those. But if you're starting a company, you have to abide by governmental rules, but you get to make up how you want your, company to operate, what you want your culture to be about.

And it certainly behooves, I think, any business in any brand to be able to be as, consistent in your values that the brand is communicating to its customers and the way that the business serves its employees because of those employees are living day to day, hour to hour. Those values in in how they show up at work and how they collaborate together.

And, then those customers are naturally going to be creating campaigns and programs and initiatives that are going to represent those values to their customers. So that's why I learned that you can really think from the inside out and set up your company with the values that are important to your brand and your business, and then that those values will be, will be lived and, and it will be lived by in the employees who will then create all the business rules and initiatives and actions that reflect those brands in the larger economy.

Daniel Burstein: Well, that's great for that internal management of the company. And that's a great story of that. And by the way, your son has a great story of his first business meeting. But I wonder when you talk about ourselves as marketers and messaging and branding, do you have any examples of how you included something from the founder in the value proposition articulation for the brand?

And I'll give you one quick example of one of my favorite examples that I've written about is, a brand called Bobby's Fine Foods. And they basically make pickles and different types of products like pickles and stuff. And on the labels is, Bobby, who's on the labels is, you know, and the logo, all of it. Bobby's Fine Foods.

And Bobby is both a fictional character in a sense, because it's this is Bobby was not actually the founder of the company. I think it was some bankers, but also a real person because this was the founders. The picture is the founders, Bobby, which means grandmother. And, so I just always thought that was a great way of just how they kind of weaved in this partly fictional, but partly real character, into the value proposition articulation of the brand.

So we're talking about founders, Catherine. And I know you work with some brands on some major heritage. Have you ever been able to get the founders, you know, something from the founder into the actual value proposition articulation?

Katherine Melchior Ray: Absolutely. So I've been staying with the story about Hannah Anderson is we created a, an idea that was part of her view of, you know, she's Swedish, so she's very concerned about the environment and sustainability and the notion and creating something that lasts so that we knew that these long fiber cotton clothes lasted well beyond, the child, the, size that they were literally going to grow out of them when there was still more life to the, to the product.

And so in order to show the quality that she she believed in, of investing in, in long term values, we actually created something which we then called the Hannah Down hand-me-down Hannah Down for Hannah Henderson program, whereby we would buy it back, we would buy back your used clothes and it was called a name for the company.

Hannah Anderson was also named for her grandmother. So Bobby and Hannah, grandma's or grandma's are great. And, and so we created a program called Hannah Down. Where to? To show customers that we had such confidence in the longevity of our product that we would literally buy it back. And so for customers who wanted to sell it back to us, we would give them a discount, on future purchases.

And then we would take those same clothes and, we wouldn't necessarily resell them, but we would then donate them to children in need. And it was just a win win. It was the first time I had really discovered this, triple bottom line. And the notion of being able to do right, not only by your customers and your employees and your shareholders, but by the economy at large.

And, I mean, it literally changed my life. And, I mean, I hate to say it, but, you know, I put this woman candidate into my will. Wow. Yeah. Because I thought, you know it. When when when all is gone. If if if I die before my children are grown because they were little at the time, this woman's values are so good, she will know what to do.

Daniel Burstein: Oh, wow. That's wonderful. Well, let's talk about the values of a brand. When we have these artificial constructs we call brands or companies. Earlier you talked about that, kind of fulcrum when it comes to a brand, there's that deep heritage it can have. But also we have to, you know, be cutting edge in some way. And I think you summed it up best with this Larsen combined audacious risk taking with care.

You said you learned it from Eve Castle, CEO of Louis Vuitton. How did you learn this from Eve?

Katherine Melchior Ray: Yeah, Eve Castle was such an amazing business man, and I have had I had the great pleasure to be able to work from home. I told you early on, that I met him up for an interview in, in in Paris for a job in Paris. But, when he understood my passion for and and competence in Japanese, he he changed the changed the game on me.

But. And this meant, to his credit. So, first of all, I was 45 minutes late for an interview with the CEO of Louis Vuitton. I kid you not.

Daniel Burstein: But in France, that's fine. In Japan it would have been bad. But France is fine right now.

Katherine Melchior Ray: And even then his secretary on my third call was like, Surely Madame, you jest, but I'll see. And to his credit, and he had nothing else to do. It was late at night and he had a dinner, so he agreed to see me. And so so we got to know each other, and. But I bring that up because it shows you the CEO like, just out of a sense of position and, humility.

He might say, I'm not going to meet with this person because she's kind of insulting me. But he didn't. He he he realized that I was a foreigner in Paris at Christmas time and, you know, got in a taxi that didn't move at all. Or maybe he didn't realize it, but he was kind enough to be able to listen to my excuse.

Anyway, he met me, but it represent the kind of things that he did. So he is the reason why Louis Vuitton is as incredibly large and powerful as it is. He took it from, the late 90s when it was really more of a traditional provider of good handbags and trunks. And he expanded it into fashion. So he was the one who said, you know, we need to expand the notion of what this brand can be and mean, and we're going to get into the fashion world.

It didn't have a history and fashion. It was it made leather goods. You know, it started as a truck maker. So, it was his idea of that to really infuse a whole new dimension of creativity and, and, and I think, excitement and the sexiness of appeal because, let's face it, trunks are trunks. Your suitcase is your suitcase.

And so it was a incredible idea, and it brought in such a charge of energy into it. And that was kind of his thinking was like, how can we take this and, explode it beyond our wildest imagination and do it while honoring the brand? So no doubt, the ideas that I got from the Baron Ultra, fulcrum or the audacity that I learned was from Eve Castle with the reputation he'd had of being able to do it.

The challenge he he, he instilled in us to think beyond the ordinary, and the support that he would give us if we did something wrong. Because, for instance, I was able to lure Madonna into the for her first Louis Vuitton shop. I mean, could you believe it? She had never been. I couldn't believe it. She'd never been into Louis Vuitton shopping, and I was doing a campaign around some photographs of her, and, my budget had gone way beyond what I was allocated, and I had to find figure out some way to do to, to get control.

But there was no way I could lower the budget. And so I realized I just have to increase the ROI, right? If you can't lower your budget, your budget is based on a certain kind of ROI. But so then if I increase the deliverable, the only way I could into livable was to get Madonna into the store. So she was coming to Tokyo for, a tour.

And I realized that's what I had to do. And so I did. I got Madonna to come and visit, a Louis Vuitton store. And, you know, I toured her through the shop. We bought stuff for her children's and Rocco, and I knew I had a bank of cameras out front because she came in through the side door just in case she showed.

And so, she wanted this, this leather jacket. And so I said, yeah, you know, just why don't you, just here. Don't worry about it. We'll send the things to the children, to your hotel, and you can just wear that. And so she literally walked out the front of the doors and knew Louis Vuitton sunglasses and a leather jacket, and it was all over the news that night, the next morning, over.

And I said, okay, to, my boss and to to Eve Castle. We're giving her that leather jacket. And he said, Catherine. Louis Vuitton doesn't discount. I was like, what? And he held the line. He said, we what? We do not discount. That's not what we do. It is a rule and we won't do it. So I was like, oh my God, it's like that, but don't you see what I did?

And so, you know, then I had to go back and then with my CFO, a CMO, best friend, as their CFO. He said, don't worry about it, Catherine. You know, we can bury it. And so we just absorbed it fully. I realized that that was what we could do. I could I could just absorb it entirely rather than, offering a discount for all of her, her clothes.

And my CEO in Japan covered me. So, you know, if Castle was one of those people who, just push people to to think beyond it, I once had to present in Paris, my, my budget. And again, remember, it was the largest business in Japan, the most profitable. If we if something went wrong, I would get a note from Bernard Arnault directly in Japan.

And have to stop a meeting and respond to Paris. So, everything we did was under scrutiny. And I presented by budget and, there were like, I felt like 12 financial people in the room, and I was the only woman. And it was in Paris. And after I went through all of this showing a measly, I think, two, 3% growth year on year eve, Castle turned to me.

Well, I squeaking out my budget right under terrible pressure, and he turned to me and he said, what would you do if you had 5 million more euros to spend in marketing? Like what? That was not what I was expecting. I was expecting people to grill me on how I was going to get our sales up to where they were not giving me more money in a, in a challenging market.

And that's how he fell off. You know, he just kind of was like, okay, we're going to pull a rabbit out of a hat. And indeed we did. The first, Louis Vuitton fashion show outside of Paris. And we created an entire dome in a park, in, in Tokyo and created, like, what was considered by de to be the top fashion show, in Japan that year.

So I think it's that kind of thinking of, either thinking out of the box or when you're down, don't stop taking risks, but be sure to. As I said, he would say no when it was a no. Be sure to honor your brand values all the time, because then people know you stand for something, they know where they stand.

And I think it was just really an incredible, an incredible lesson to to work with someone like him who, who shared such incredible business acumen on the one hand. And yet such humanity on the other.

Daniel Burstein: Well, one of the things I'm really interesting when you're talking about that is a journey. Examples A lot of a lot of these campaigns are the choices we make, the specific choices we make in different decisions. And I wonder if you had any examples where you had to make a choice between balancing that legacy and that edginess, because when you talk about Eve Cosell, you mentioned he kind of brought Louis Vuitton into the fashion world.

I think he was. You mention he's famous for hiring Marc Jacobs as his first creative director. Right. So Marc Jacobs, there is, a brand there, kind of of who that individual is, and then there a brand of Louis Vuitton's legacy. And so I just wonder if there was any choices or decisions or thoughts you could take into how you had to kind of balance those two worlds and make them gel together?

Katherine Melchior Ray: Well, as I said, I think the story of the Art of travel is a really good example of that. So we were going more and more into trend and fashion. And it was realizing through market research and sales data that we couldn't continue in this direction. So, you know, what do you do? Is it that your innovation is just misaligned?

Do you just need more innovation? Should we align with a different fashion director or a different artist at the time we were working with Murakami, so was it that, you know, Murakami had lost his luster? I mean, you know, what was it? And I went in the other direction. I realized that we needed to balance. It wasn't a question of innovation on the trend side.

It was about we were creating new excitement around our long lasting values. So I think that's that's an example of kind of saying, okay, I have all these tools in my toolkit. Which one do I want to use now? And you know, there are no answers for this, right? Everyone and all these people might have different opinions. Research might lead you in certain directions or certain other directions.

But as we talked about with history, when you learn how to craft the narrative, you know you can learn how to choose the data you want for the argument that you want. But on the other hand, you have to also stay open minded enough that you don't create subjective viewpoints. And misread the opportunity that might be sitting in front of you.

So, that's why marketing is so fun, because there are so many opportunities and there are so much data. If, and ideas out there, it's really being able to choose the right one at the right time for the right audience, in the right market.

Daniel Burstein: Well, you mentioned the word toolkit, Catherine, and I wonder if you could summit all up to us, what is a toolkit that we need as marketers? What are the key qualities of an effective marketer?

Katherine Melchior Ray: Well, okay. The tools are always changing. So if I think of I that is the latest tool that we're all using and I like, I, I'm a little concerned about it going forward because if I look at young people, they don't know how to get somewhere without Google Maps. So I think they have outsourced their geographical spatial ability.

And I think, well, what does that mean for AI and our writing ability? I find it myself too. I just wrote a book, and I find that, you know, I'm losing confidence in my own writing because they can give it to me and it. Yeah, it's not, it's not 100%, but it's 80, and I saved 80% of my time.

So what does that telling us? What are those choices that we're making? But so tools are always changing. And I think you need to always embrace the tools, because getting in early and testing things gives you an enormous advantage, right? The early mover advantage is huge. But I think stepping back when I think about what is the most important thing for a marketer, it's really the balance.

It's back to a balance. Right? And I think it's a left brain and right brain balance. I, I was told once when I was young and now I understand, I was told before I was an CMO, when I was a young marketer, I was told I did some test for a headhunter, was trying to help me find a job, and he had me do this little assessment and he was like, oh my gosh, I've never seen this.

And I said, what? And he said, you are absolutely 5050 left brain, right brain. And I'm like, what does that mean? And he said, well, that's what marketing is. Marketing is equal parts left brain analysis and right brain creative. And I think that that makes a lot of sense to me because and and, you know, we have to be able to look at the data with a very, objective and analytical brain.